OBS Studio Gets A New Renderer

How OBS Adopted Metal

Starting with OBS Studio 32.0.0 a new renderer backend based on Apple's Metal graphics API is available for users to test as an experimental alternative to the existing OpenGL backend on macOS. This marks an important step in OBS Studio's development to adapt one of the modern APIs that deliberately broke with the past to unlock better performance and efficiency gains for end users, but also require fundamental changes to how an application interacts with a GPU.

These fundamental changes were necessary to achieve the goals of lower overhead, faster performance, and to better represent the way that modern GPUs actually work, particularly when the GPU is used for more than just 3D rendering. Yet other changes were also necessary due to the way Metal was specifically designed to fit into Apple's operating systems.

Due to the sheer amount of information around this topic, it made sense to split it into separate posts:

- The first post (this one) will go into specific challenges and insights from writing the Metal backend for OBS Studio.

- The second post will look at the history of 3D graphics APIs, their core differences, and how the design of the new generation creates challenges for existing renderers like the one in OBS Studio.

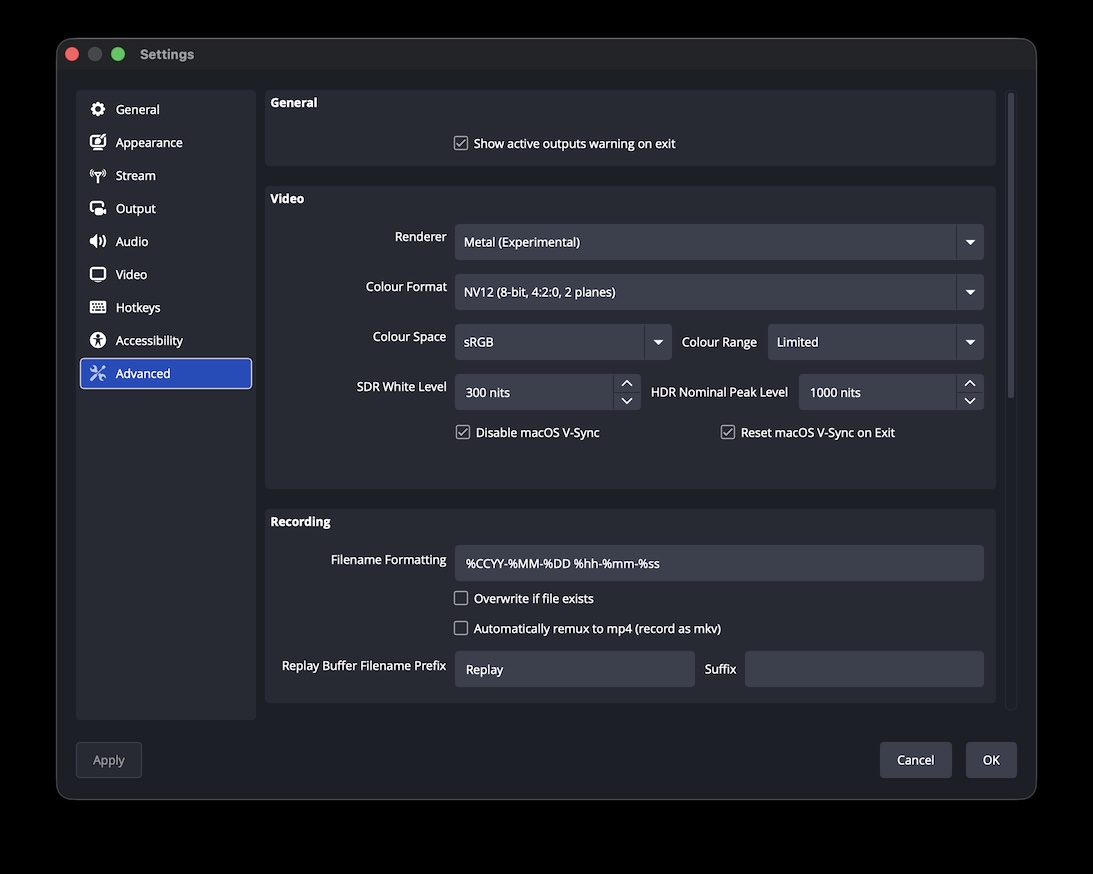

The Metal backend is explicitly marked as "Experimental" in the application because it has some known quirks (for which no good solutions have been found yet, more about that below) but also because it has not yet been tested by a larger user audience. The OpenGL renderer is still the default choice offered to users and will be available for the foreseeable future, but we still would like to invite users to try out the Metal backend for themselves, and report any critical bugs they might encounter.

Better yet, if you happen to have prior experience working with Metal on Apple Silicon platforms (including iPhones), we'd be happy to hear feedback about specific aspects of the current implementation or even review pull-requests with improvements to it.

Part 1.1: The Why Of Metal

In June 2014 Apple announced (and - more importantly - also released to developers) the first version of Metal for iPhones with Apple's A7 SOC, extending its support to current Macs of the time in 2015. Thus Metal was not only available on what became later known as "Apple Silicon" GPUs, but also Intel, AMD, and NVIDIA GPUs, being the first "next generation" graphics API to support all mainstream GPUs of the time.

Metal combined many benefits to Apple specifically: The API was based on concepts and ideas that not only already found their way into AMD's "Mantle" API (which was announced in September 2013) but had also been discussed for and adopted to some degree in the existing graphics APIs (OpenGL and Direct3D) at the time. But as a new API written from scratch it had the chance to omit all the legacy aspects of existing APIs and fully lean into these new concepts. It was able to provide the performance gains unlocked by this different approach and as it was originally designed for iOS and macOS, an entirely new API implemented in Objective-C and Swift (the latter of which was also introduced in 2014).

While OpenGL did (and still does) provide a well-established C-based API, it incorporates a binding model that is considered inelegant by many. Direct3D to this day uses a C++-based object-oriented API design (primarily via the COM binary interface), making it easier for developers to keep track of state and objects in their application code. Notably existing APIs in COM-based systems are not allowed to change, instead new variants have to be introduced, providing a decent amount of backwards-compatibility for applications originally written for older versions of Direct3D.

Metal takes Direct3D's object-oriented approach one step further by combining it with the more "verbal" API design common in Objective-C and Swift in an attempt to provide a more intuitive and easier API for app developers to use (and not just game developers) and to further motivate those to integrate more 3D and general GPU functionality into their apps. This lower barrier of entry was very much the point of earlier Metal versions, which combined the comparatively easier API with extensive graphics debugging capabilities built right into Xcode, providing developers with in-depth insights into every detail of their GPU processing (including built-in debugging of shader code) in the same IDE used for the rest of their application development.

Part 1.2: Differences In API Design

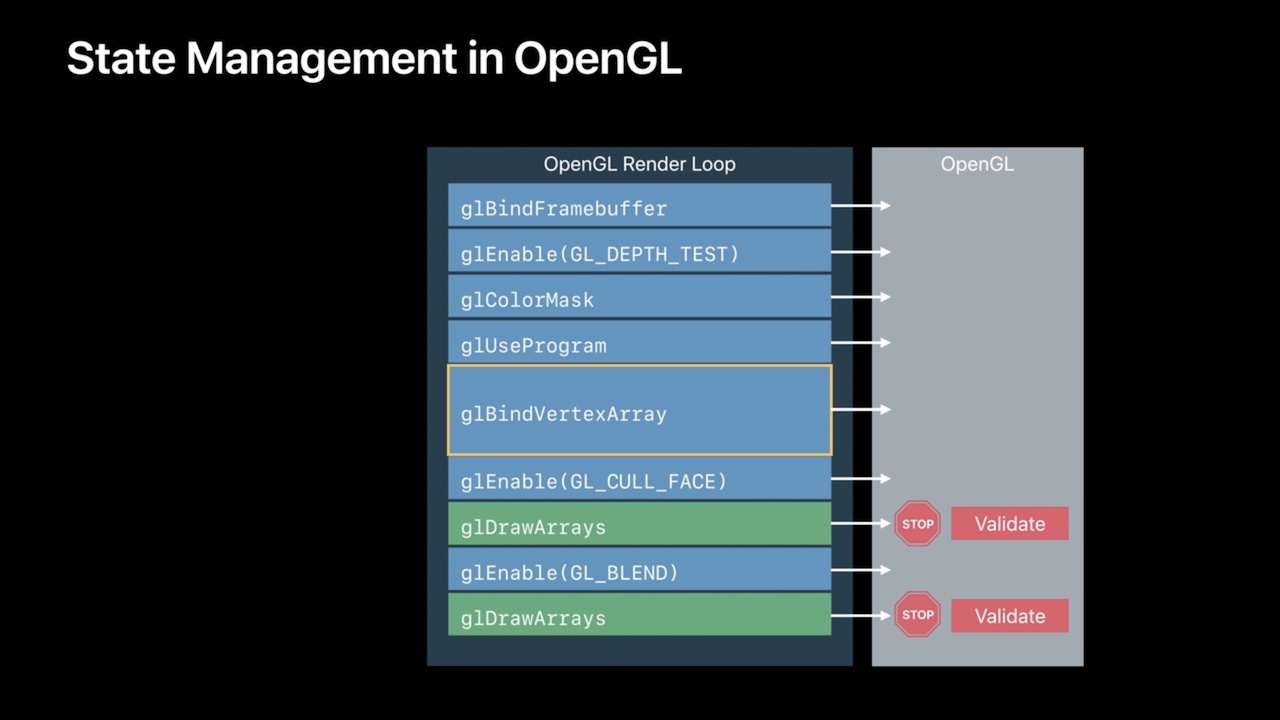

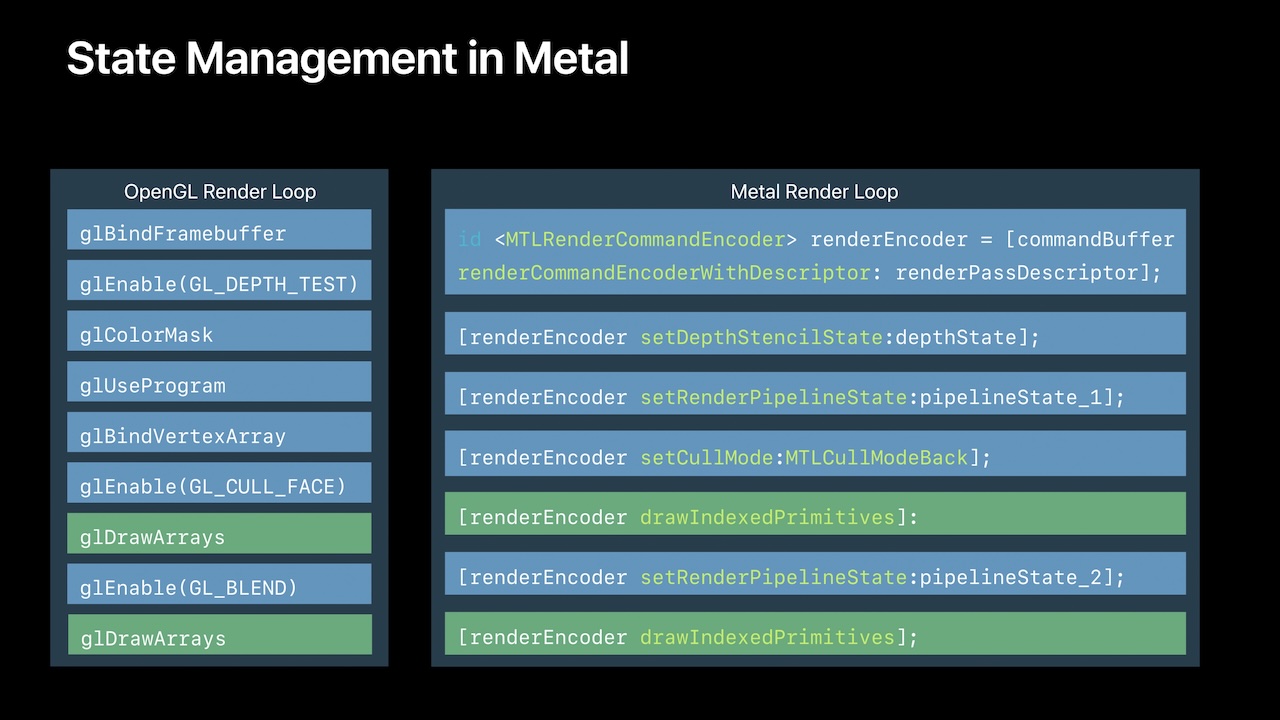

All modern APIs share the same concepts and approaches in their designs, which attempt to solve a major design issue of OpenGL and Direct3D:

- The old APIs took care of a lot of resource management and synchronization for the developer, "hiding" much of the actual complexity involved in preparing the GPU for workloads.

- The old APIs presented the GPU as a big state machine (particularly OpenGL) where the developer can change bits and pieces between issuing draw calls.

- Due to the possibility to change bits and pieces of a pipeline at will, the old APIs had to check if the current "state" of the API is valid before issuing any work to the GPU, adding considerable overhead to the API "driver".

- The new APIs removed most of that and now require developers to manage their resources and synchronization themselves, only providing methods to communicate their intent to the API and thus the GPU.

- The new APIs present the GPU as a highly parallelized processing unit that can be issued a list of commands that will be added to a queue and are then picked up by the GPU, "drawing" just being one of many operations.

- To avoid having to re-validate the pipeline state before each draw call, pipelines have become immutable objects, whose validity is checked once during their creation, removing the overhead from draw commands using the pipeline, leaving some overhead whenever the pipelines themselves are switched.

Of course there are many other differences (large and small) but those are the ones that had the most impact on the attempt to write a "next generation" graphics API backend for OBS Studio. The current renderer is obviously built around the way the old APIs work (particularly Direct3D) and thus makes certain assumptions about the state the APIs will be in at any given point in time. The issue is that those assumptions are not correct as soon as any of those new APIs are used and a lot of the work that the APIs used to do for OBS Studio now has to be taken care of by the application itself.

So a decision had to be made: Either the core renderer can be updated or even rewritten to take care of the responsibilities expected by the modern APIs, adapting more modern "indirect drawing" techniques in Direct3D and OpenGL to make them more compatible with that approach (making those renderers potentially more performant as well), or put this additional work entirely into the backend for one of the new APIs, leaving the core renderer as-is. At least for the Metal backend, the second path was chosen.

Part 1.3: The Expectations Of OBS Studio's Renderer

Before the new release, OBS Studio shipped with two graphics APIs: Direct3D on Windows and OpenGL on Linux and macOS. This is achieved by having a core rendering subsystem that is (for the most part) API-independent and requires an API-specific backend to be loaded at runtime. This backend then implements a generic set of render commands issued by the core renderer and translates those into the actual commands and operations required by its API. That said, the core renderer has some quirks that become apparent once one tries to add support for an API that works slightly different than it might expect:

- As OBS Studio's shader files are effectively written in an older dialect of Microsoft's High Level Shader Language (HLSL), every shader needs to be analyzed and translated into a valid variant for the modern API at runtime.

- Shaders are expected to use the same data structure as input and output type, as well as support global variables.

- The application expects all operations made by the graphics API to be strictly sequential, and to always execute operations involving the same resources strictly in order of submission to the API.

- OBS Studio's texture operations (creating textures from data loaded by the application, updating textures, reading from textures, and more) are directly modelled after Direct3D's API design. Any other API needs to work around this expectation and do housekeeping "behind the scenes" to meet it.

- OBS Studio also expects to be able to render previews (such as the program view, the main preview, the multi-view, and others) directly at its own pace (and framerate), expecting every platform to effectively behave like Windows and provide "swapchains" with the "discard model" used by DXGI, and thus is not decoupled from the render loop for the video output.

Most of these issues either fall into the realm of shaders or the API design itself, all of which had to be overcome by the Metal backend.

Part 1.3.1: Transpiling Shaders

OBS Studio makes extensive use of shader programs that run on the GPU to do efficient image processing. Both libobs (OBS Studio's main library that includes the core renderer) as well as plugins like the first-party obs-filters plugin provide their own "effect" files, which are implemented using the HLSL dialect mentioned above.

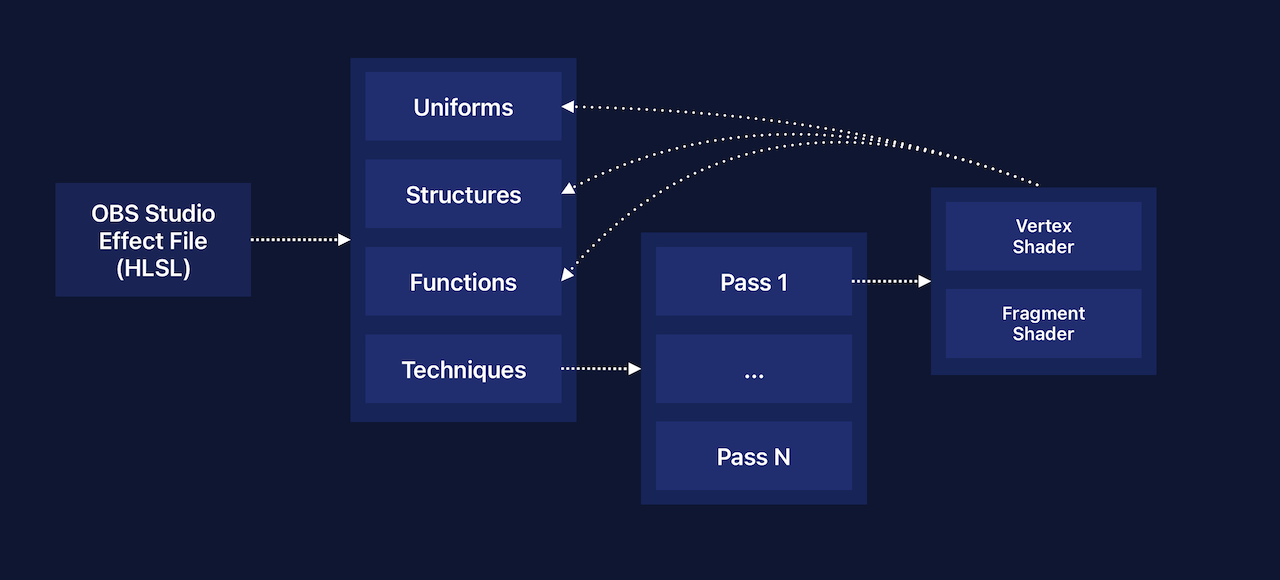

These effects files contain "techniques", each potentially made of up of a number of render passes (although all current OBS Studio effect files use a single pass) that provide a vertex and fragment shader pair. The vertex shader is the little program a GPU runs for every vertex (a "point" of a triangle) to calculate its actual position in a scene relative to a camera looking at it. The fragment shader (also called "pixel shader" in Direct3D) calculates the actual color value for each fragment (a visible pixel in the output image).

To make these files work with OpenGL and Direct3D, they need to be converted into bespoke shader source code for each "technique" first, which OBS Studio achieves through multiple steps:

- Each effect file is parsed in its entirety and converted into a data structure representing each "part" of the effect file:

- The "uniforms", that is data (or a data structure) that is updated by application code at every rendered frame.

- The "vertex" or "fragment" data (usually a data struct) that is kept in GPU memory.

- Texture descriptions (textures can be 1-, 2-, or 3-dimensional) and sampler descriptions (samplers describe how a color value is read from a texture for use in a shader).

- The shader functions, including their return type and argument types.

- Additionally each technique (and pass(es) within) are parsed into a nested data structure:

- OBS Studio will then iterate over every technique and its passes to pick up the names of the vertex and fragment shader functions mentioned in each.

- The uniforms, shader data, as well as the texture and sampler descriptions, are shared among each technique within the same file. The created data structures are used to re-create the (partial) HLSL source code that was parsed originally.

- The shader functions and their content are then copied and a "main" function is generated (as the entry-point for the shader) calling the actual shader function. The generated final HLSL string is kept as the shader representation of each "technique".

- Each technique is sent in its HLSL form to each graphics API and is then transpiled into its API-specific form:

- For Direct3D this means replacing text tokens with their more current variants.

- For GLSL this means parsing the HLSL string back into structured data again, before iterating over this data and composing a GLSL shader string from it. As shader function code is not analyzed, it needs to be parsed word-for-word and translated into GLSL-specific variants if necessary.

UPDATE (January 2026): After this article was posted, we were informed that global variables were supported in the Metal Shading Language (MSL), starting with version 3.1.

While the workarounds documented below might still be necessary when using an older version of MSL, the UniformData in GPU buffer 30 can be assigned directly:

constant UniformData& constant uniforms [[buffer(30)]];

The view projection matrix could then be accessed in any scope via uniforms.ViewProj and would not need to be explicitly passed as a function argument through the different layers of the shader. The usual caveats of global variables apply, but in this case the global variable is strictly read-only by being a constant reference to data in the constant address space.

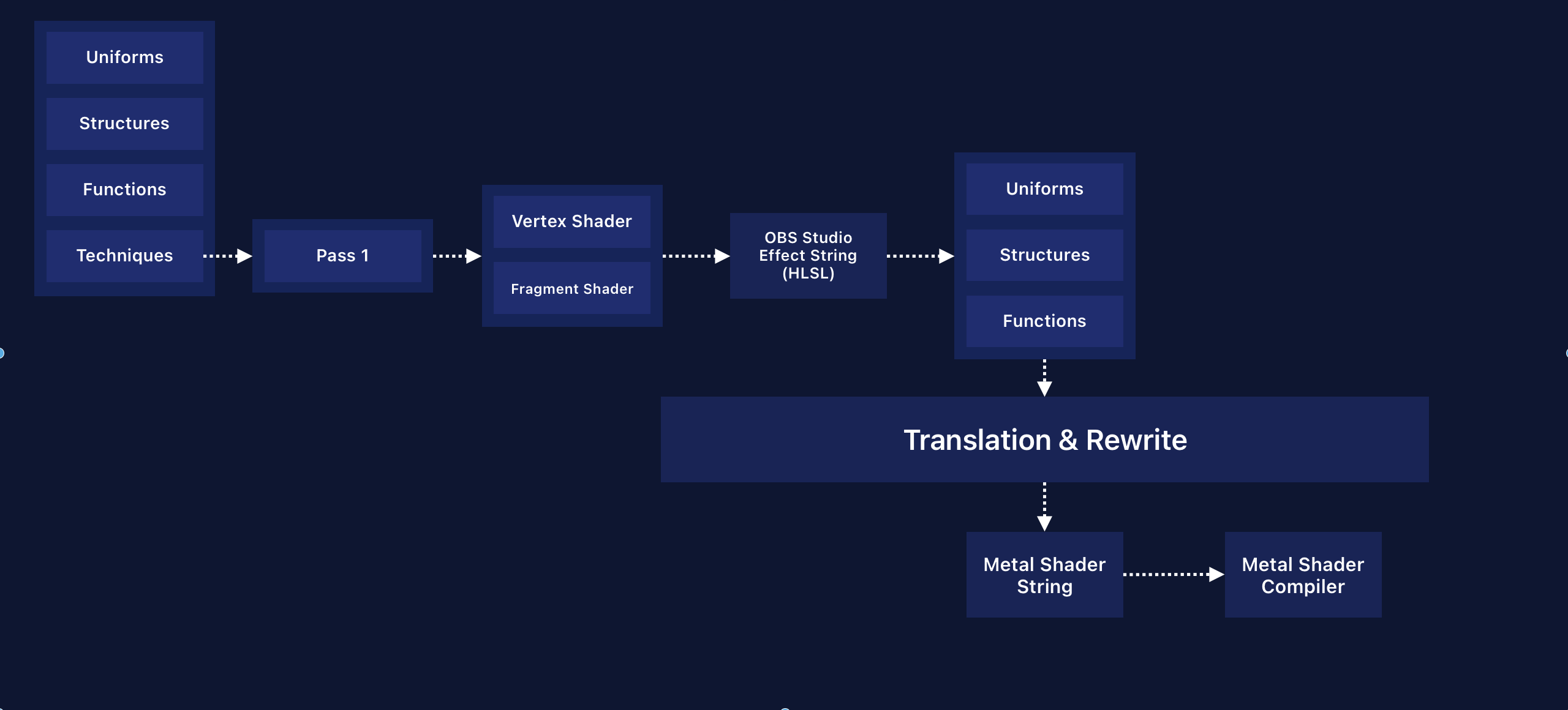

Adapting this process for Metal led to a few challenges, born out of the stricter shader language used by the API:

- MSL is stricter around types and semantics:

- Direct3D uses "semantics" to mark parts of shader data structs and give them meaning, like

TEXCOORD0,COLOR0, orSV_VertexID, while OpenGL uses global variables that shader code instead reads from or writes into. - Metal uses a similar semantics-based model as Direct3D via attributes, but their use is more strict. Some attributes are allowed for input data, but not for output data.

- Thus the same struct definition cannot be used as input and output type definition, instead the single struct type used by HLSL needs to be split into two separate structs for MSL.

- Every function's content then needs to be scanned for any use of the struct type and needs to be replaced with the appropriate input or output variant.

- Direct3D uses "semantics" to mark parts of shader data structs and give them meaning, like

- MSL has no support for global variables:

- This means that "uniforms" as used by Direct3D (and set up by OBS Studio's renderer) cannot be used by Metal - uniform data needs to be provided as a buffer of data in GPU memory.

- This buffer of data can be referenced as an input parameter to a shader function, thus any use of the global variable (used by HLSL and GLSL) needs to be replaced with a use of the function argument.

- However any other function called by the "main" shader function also accessing a global variable needs this local variable passed explicitly to it, thus - once again - every function's code needs to be parsed and analyzed.

- Any time a function uses a global, it needs to have a new function argument added to its signature to accept the "global" data as an explicit function parameter.

- Any time a function calls a function that uses a global, it also needs to have its signature changed to accept the data explicitly and also change the call signature to pass the data along.

And these are just two examples of major differences in the shader language that require the transpiler to almost rewrite every effect file used by libobs.

Here's a trivial example, OBS Studio's most basic vertex shader that simply multiplies each vertex position with a matrix to calculate the actual coordinates in "clip space" (coordinates that describe the position as a percentage of the width and height of the camera's view):

uniform float4x4 ViewProj;

struct VertInOut {

float4 pos : POSITION;

float2 uv : TEXCOORD0;

};

VertInOut VSDefault(VertInOut vert_in)

{

VertInOut vert_out;

vert_out.pos = mul(float4(vert_in.pos.xyz, 1.0), ViewProj);

vert_out.uv = vert_in.uv;

return vert_out;

}

VertInOut main(VertInOut vert_in)

{

return VSDefault(vert_in);

}In this shader the view projection matrix is provided as a global variable called ViewProj and it's used by the VSDefault shader function. The Metal Shader variant needs to be a bit more explicit about the flow of data:

#include <metal_stdlib>

using namespace metal;

typedef struct {

float4x4 ViewProj;

} UniformData;

typedef struct {

float4 pos [[attribute(0)]];

float2 uv [[attribute(1)]];

} VertInOut_In;

typedef struct {

float4 pos [[position]];

float2 uv;

} VertInOut_Out;

VertInOut_Out VSDefault(VertInOut_In vert_in, constant UniformData &uniforms) {

VertInOut_Out vert_out;

vert_out.pos = (float4(vert_in.pos.xyz, 1.0)) * (uniforms.ViewProj);

vert_out.uv = vert_in.uv;

return vert_out;

}

[[vertex]] VertInOut_Out _main(VertInOut_In vert_in [[stage_in]], constant UniformData &uniforms [[buffer(30)]]) {

return VSDefault(vert_in, uniforms);

}As explained above, the single VertInOut struct had to be split into two separate variants for input and output, as the attribute(n) mapping is only valid for input data. It uses a pattern more common in modern APIs where memory is typically organized in larger heaps into which all other data (buffers, textures, etc.) is placed and referenced. In this case the stage_in decoration allows the developer to access vertex or fragment data for which a vertex descriptor had been set up and is used for convenience. Otherwise the variable would just represent a buffer of GPU memory.

To tell Metal which part of the output structure contains the calculated vertex positions, the corresponding field has to be decorated with [[position]] or return a float4 explicitly. Every vertex shader has to do one or the other, as it would otherwise fail shader compilation.

The uniform global used by HLSL is transformed into a buffer variable: The uniform data is uploaded into the buffer in slot 30 and referenced by the [[buffer(30)]] decorator and uses the ampersand (&) to make it a C++ reference using the constant address space attribute, which marks this reference to be read-only. The uniforms reference is also passed into the VSDefault function, as the transpiler detected that the function accesses ViewProj within its function body, and thus adds it as an argument to the function signature and converts the reference of ViewProj into the correct form uniforms.ViewProj.

Similar work has to be done for all those cases where GLSL or HLSL will opportunistically accept data with the "wrong" types and alias or convert them into the correct one. Metal does not allow this, the developer has to put any such conversion into code explicitly and also requires any function call to match the function signature. Here is one such example:

float PS_Y(FragPos frag_in)

{

float3 rgb = image.Load(int3(frag_in.pos.xy, 0)).rgb;

float y = dot(color_vec0.xyz, rgb) + color_vec0.w;

return y;

}In this example the HLSL shader uses the Load function to load color values from a texture and passes in a vector of 3 signed integer values. A valid Metal Shader variant would look like this:

float PS_Y(FragPos frag_in, constant UniformData &uniforms, texture2d<float> image) {

float3 rgb = image.read(uint2(int2(frag_in.pos.xy)), uint( int( 0))).rgb;

float y = dot(uniforms.color_vec0.xyz, rgb) + uniforms.color_vec0.w;

return y;

}The signature of the corresponding read function in MSL requires a vector of 2 unsigned integer values and a single unsigned integer. Thus the transpiler needs to detect any (known) invocation of a function that uses type aliasing or other kinds of type punning and explicitly convert the provided function arguments into the types required by the MSL shader function, in this case converting a single int3 into a pair of uint2 and uint and ensuring that the data passed into the uint constructor is actually of a specific type that can be converted.

These and many other changes are necessary because MSL is effectively C++14 code and thus requires the same adherence to type safety and function signatures as any other application code written in C++. This allows sharing header files of data type and structure definitions between application and shader code, but also requires shader code to be more correct than it had to be for HLSL or GLSL in the past. And in the case of OBS Studio, the transpiler has to partially "rewrite" the HLSL shader code into more compliant MSL code at runtime.

Part 1.3.2: Pretending To Be Direct3D

The next hurdle was to simulate the behavior of Direct3D inside the Metal API implementation. As it was deemed infeasible to rewrite the core renderer itself, it must be "kept in the dark" about what actually happens behind the scenes.

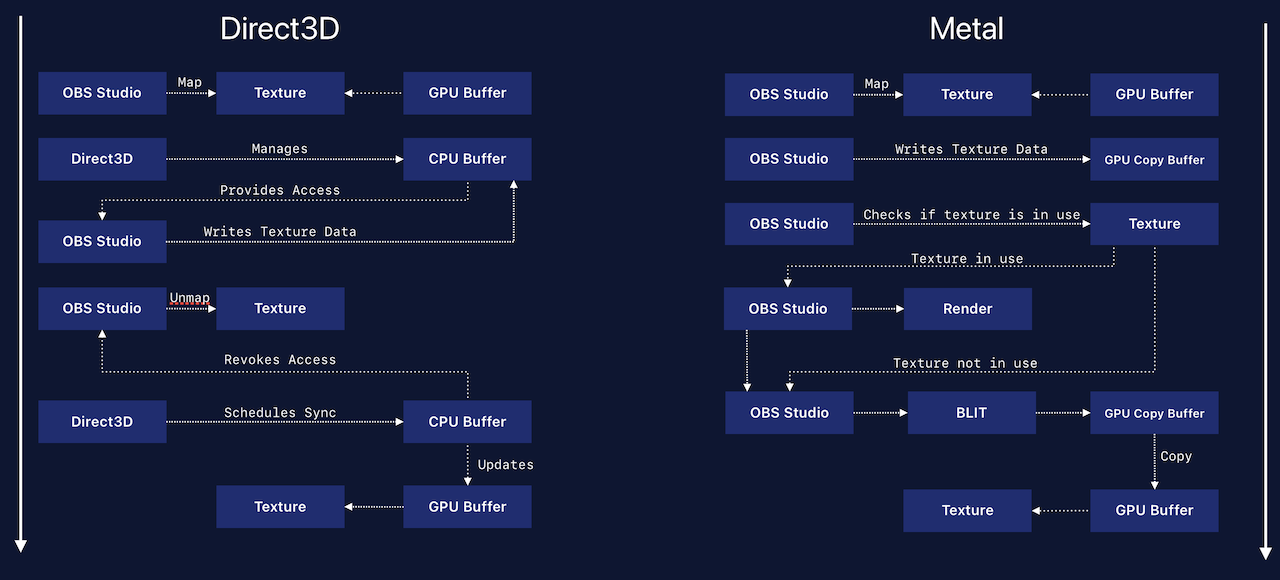

One of the main jobs OBS Studio has to do for every video frame is convert images (or "frames") provided by the CPU into textures on the GPU, and - depending on the video encoder used - convert the final output texture back into a frame in CPU memory that can be sent to the encoder. In Direct3D this involves the "mapping" and "unmapping" of a texture:

- When a texture is "mapped" it is made available for the application code in CPU memory.

- When the texture is mapped for writing, Direct3D will provide a pointer to some CPU memory that it has either allocated directly or had been "lying around" from an earlier map operation. OBS Studio can then copy its frame data into the location.

- When the texture is mapped for reading, Direct3D will provide a pointer to CPU memory that contains a copy of the texture data from GPU memory. OBS Studio can copy this data into its own "cache" of frames.

- When OBS Studio is done with either operation, it has to "unmap" the texture. The provided pointer is then invalidated and any data pointed to it can and will be changed randomly.

By itself a naïve implementation of this operation can have severe consequences: When a texture is mapped for writing, any pending GPU operation (e.g., a shader's sampler reading color data from it) might be blocked from being executed as the texture is still being written to. Likewise when a texture is mapped for reading, any pending CPU operation (e.g., copying the frame data into a cache for the video encoder) might have to wait for any GPU operation that currently uses that texture.

As part of its resource tracking behind the scenes, Direct3D 11 keeps track of texture access operations and will try to keep any such interruptions to a minimum, which leads specifically to the kind of overhead the modern APIs try to avoid:

- When a texture is mapped for writing, Direct3D will keep track of the mapping request and provide a pointer to get the data copied into, even while the texture is in use, and schedule a synchronization of the texture data.

- Once the texture is unmapped, Direct3D will upload the data to GPU memory and once this has taken place, schedule an update of the texture with the new image data.

- If any consecutive draw call that uses the same texture was issued by the application code after the unmapping, Direct3D will implicitly ensure that all pending GPU commands are scheduled and thus the texture update will take place before any consecutive GPU command might access the same texture.

- When a texture is mapped for reading, Direct3D will also ensure that all pending GPU commands writing to that texture are executed first to ensure that the copy it will provide will represent the result of any draw commands issued by the application before that.

- These are just examples of what might happen, as the specifics are highly dependent on the current state of the pipelines, the internal caches of the API's "driver" and other heuristics.

OBS Studio's entire render pipeline is designed around the characteristics of the map and unmap commands in Direct3D 11 and expect any other graphics API to behave in a similar way. Metal (as other modern APIs) does not do all of this work (Metal 3 will indeed still do hazard tracking of resources, but developers can opt-out of this behavior, and Metal 4 removed it entirely) and thus the API-specific backend has to simulate the behavior of Direct3D 11 in its own implementation:

- When a texture is mapped for writing, a GPU buffer is opportunistically set up to hold the image data.

- As the Metal backend is only supported on Apple Silicon devices, GPU and CPU share the same memory. This means that a pointer to the buffer's memory can be directly shared with the renderer,

- When the texture is "unmapped", a simple block transfer (or blit) operation is scheduled on the GPU to copy the contents of the GPU buffer into the GPU texture. The unmap operation will "wait" until the blit operation has been scheduled on the GPU to prohibit the renderer from issuing any new render commands which would potentially run in parallel.

- When a texture is mapped for reading, the same pointer to the GPU buffer is shared with application code. As the buffers are never used by any render command directly, no hazard tracking is necessary. An "unmapping" thus does nothing.

- "Staging" a texture for reading thus only requires scheduling a blit from the source texture into its associated staging buffer (as buffers and textures are effectively the same thing and differ only by their API). To ensure that no further render commands are issued by the application, the copy operation is made to wait until it is completed by the GPU, but also has to ensure that if the source texture has any pending render commands, that those are scheduled to be run on the GPU explicitly.

The same applies to other operations closely following Direct3D's design: To ensure that the Metal backend reacts in a way that meets the way OBS Studio's renderer expects, it had the "hidden" functionality of Direct3D implemented explicitly, particularly the tracking of texture use by prior render commands before any staging takes place.

Part 1.4: But Wait, There's More (Issues)

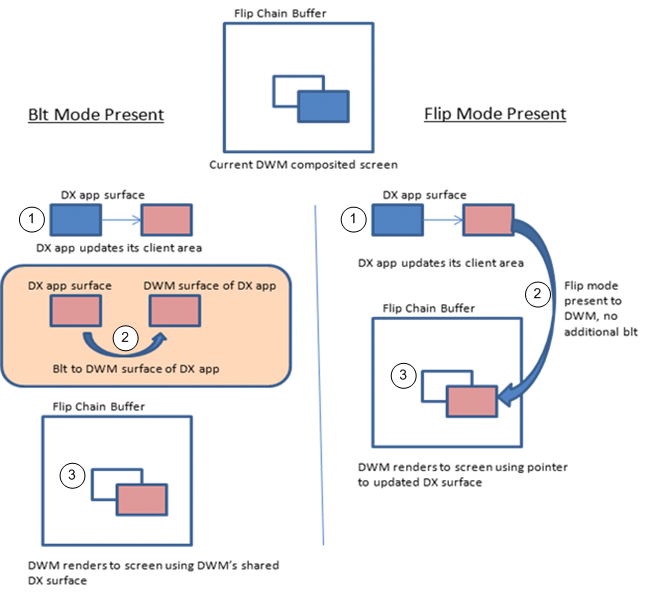

One major reason why the backend is considered "experimental" is due to the way its preview rendering had to be implemented for now. To understand the core reason for those issues, it is important to first understand how OBS Studio expects preview rendering to work, which closely shaped by the way DXGI (DirectX Graphics Infrastructure) allows applications to present 3D content on Windows. DXGI swapchains hold a number of buffers with image data created by the application, one of which the application can ask to be "presented" by the operating system.

To avoid an application potentially generating too many frames than can be presented (and thus potentially blocking the application), DXGI swapchains can be set to have a "discard" mode and a synchronization interval of 0, which effectively allows an application to force the presentation of a back buffer immediately (without waiting for the operating system's own screen refresh interval) and because the contents of the buffer are discarded, it becomes available to be overwritten by the application with the the next frame's data.

Unfortunately this is the opposite of how Metal (or more precisely Metal Layers) allows one to render 3D contents into application windows: With the introduction of ProMotion on iPhones and Macbooks, macOS controls the effective frame rates used by devices to provide fluid motion during interaction, but potentially throttle the desktop rendering to single digit framerates when no interaction or updates happen. This allows iOS and macOS to limit the operating system framerate (and the framerate of all applications within it) when the device is set to "low power" mode and is thus not designed to be "overruled" by an application (as it would allow such an application to violate the "low power" decision made by the user).

Thus applications cannot just render frames to be presented by the OS at their own pace, instead they have to ask for a surface to render to and the number of surfaces an application can be provided with is limited. This means that if OBS Studio is running at twice the frame rate of the operating system, it would exhaust its allowance of surfaces to render into. And because OBS Studio renders previews as part of its single render loop, any delay introduced by a preview render operation also stalls or delays the generation of new frames for video encoders.

The solution (at least for this first experimental release) was for OBS Studio to always render into a texture that "pretends" to be the window surface to allow the renderer to finish all its work in its required frame time. Then a different thread (running globally for the entire app with a fixed screen refresh interval) will pick up this texture, request a window surface to render into, and then schedule a block transfer (blit) to copy the contents into the surface. This also requires explicit synchronization of the textures' use on the GPU to ensure that the "pretender" texture is fully rendered to by OBS before the copy to the surface is executed.

In a nutshell: Whenever the operating system compositor requires a refresh, a separate thread will wait for OBS Studio to render a new frame of the associated preview texture and only once that has happened, the texture data is copied into the surface provided by the compositor. But as the preview rendering is now decoupled from the main render loop, framerate inconsistencies are inevitable. The kernel-level timer provided by the operating system will not align with OBS Studio's render loop (which requires the render thread to be woken up when it's calculated "time for the next frame" has been reached) and thus either a new frame might have been rendered in time or an old frame could not be copied in time.

Starting with macOS 14, the approach suggested by Apple would require OBS Studio to decouple these intervals even further, as every window (and thus potentially every preview) will have its own independent timer at which the application will receive a call from the operating system with a surface ready to be rendered into, which would bring a whole new set of potential challenges as it's even further removed from how OBS Studio expects to be able to render previews in the application.

Part 1.5: The Hidden Costs Of Modern Graphics APIs

The complexity of the endeavor was high and took several months of research, trial and error, bugfixing, multiple redesigns of specific aspects, and many long weekends. During the course of development it also became clear why some applications that simply switched from OpenGL to Vulkan or Direct3D 11 to Direct3D 12 might have potentially faced worse performance than before, seemingly contradicting those API's promise of improved performance.

Part of the reason is that a lot of the work that had been taken care of the by API's drivers are now application responsibilities and thus need to be taken care of by developers themselves. This however requires a more intimate understanding of "how the GPU works" and familiarization with those parts of Direct3D or OpenGL that were purposefully hidden from developers up to this point. And it also requires a more in-depth understanding of how the render commands interact with each other, what their dependencies are, and similarly how to encode and communicate these dependencies to the GPU to ensure that render commands are executed in the right order.

In the case of the Metal backend, this means that a certain amount of overhead that was removed from the API itself had to be reintroduced into the backend again, as even though it would be in a far better position for adoption, the core renderer was not available for a rewrite. Nevertheless even with this overhead, the Metal backend provides multiple benefits:

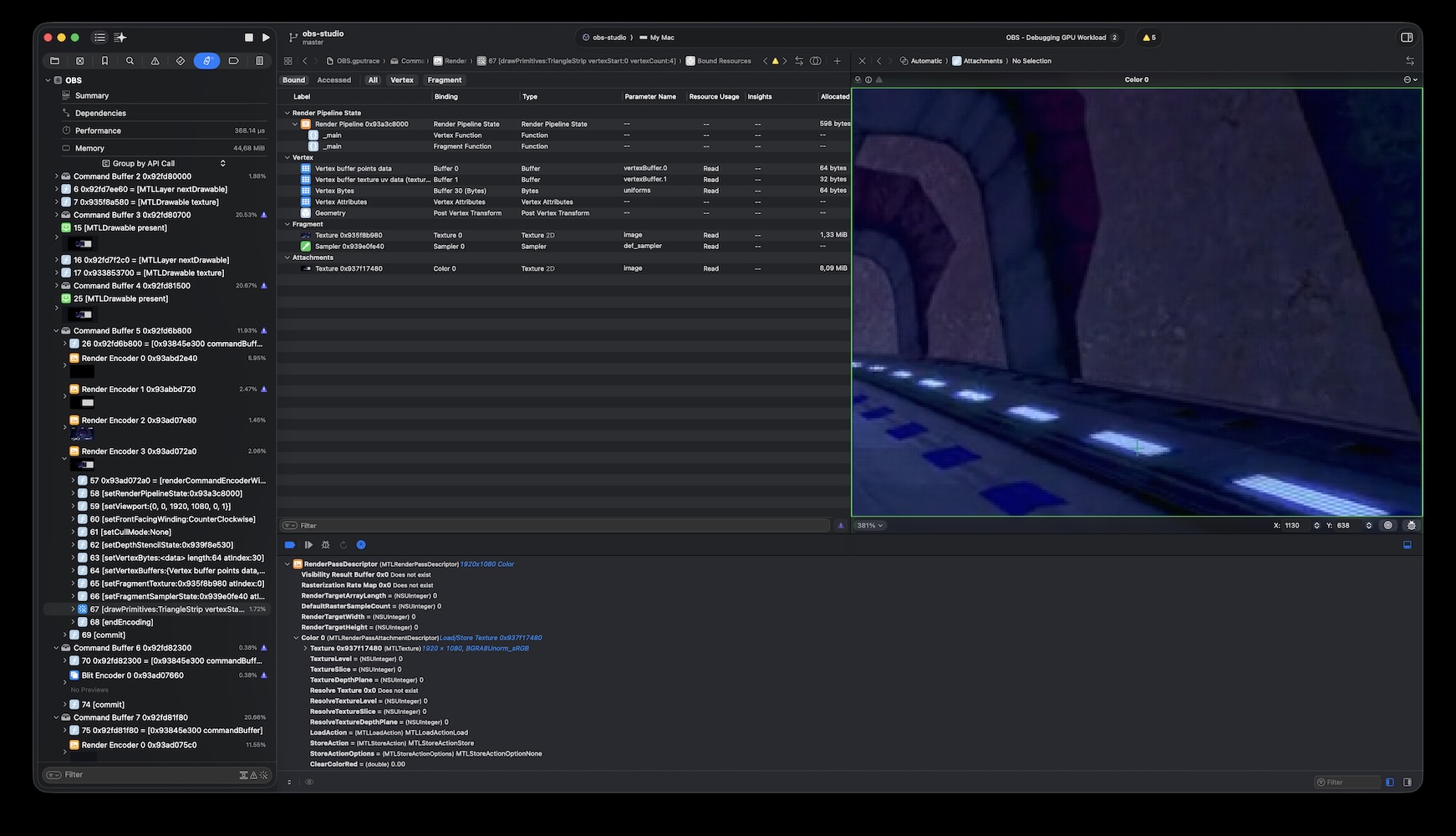

- In Release configuration and even in its non-optimized current form, it performs as well or even better as the OpenGL renderer.

- In Debug configuration it provides an amazing set of capabilities to analyze render passes in all their detail, including shader debugging, texture lookups, and so much more.

- As it's written in Swift, it uses a safer programming language than the OpenGL renderer, one that is at the same time easier and less time consuming to work with.

- Because preview rendering is effectively handled separately from the main render loop, the Metal renderer enables EDR previews on macOS for high-bitrate video setups.

As far as maintenance of the macOS version of OBS Studio is concerned, the Metal backend brings considerable benefits as Xcode can now provide insights that haven't been available to developers since the deprecation of OpenGL on all Apple platforms in 2018. But it is due to these complexities that the project would like to extend an invitation to all developers (and users that might be so inclined) to provide feedback and suggestions for changes to improve the design and implementation of the Metal backend to first move it out of the "experimental" stage and later make it the default graphics backend on macOS.